There are 32 students in the International Course of my school. Most of the classes are broken up by level and I have a lot of freedom in regards to what and how I teach the different levels. Before summer break, I did a series of three reading classes with the lower-intermediate students which ended by asking them to write a short summary of a simplified newspaper article we had been working with during the lesson. I cradled my head in despair was pretty shocked when a majority of students turned in nothing but a few sentence fragments. I was pretty sure that the problem wasn’t comprehension, as we had run through a number of activities which left both me and them confident they understood what was in the articles. And the articles themselves had come from Sandra Heyer’s All New Easy True Stories, which I had picked, in part, because I thought the simple grammar could serve as pretty good target examples for when students were given writing assignments.

But after thinking about it during summer vacation, it seemed to me that I had been expecting quite a lot of my students. Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it usually helps if expectations are realistic. And considering the fact that most of my students come from a non-academic background, missed large chunks of their middle school career, and are rarely asked to summarize in Japanese, let alone English, my expectations in this case were just a tad bit on the flowers-spontaneously-blooming-in-the-desert variety.

So just what makes summarizing so difficult? Well, as Kirkland and Saunders (1991, p. 100) rightly point out, “The L2 skills needed in summarizing include adequate reading skills and comprehension level plus adequate control of grammar, vocabulary, and writing skills to manipulate and express the information.” And to make things even more difficult, summarizing, “is highly interactive and recursive process.” It requires moving between reading and writing a number of times, holding portions of the text in memory, manipulating it, and comparing and contrasting it with what is being produced in the summary. In light of this, it makes sense that most articles focused on summarizing are for the EAP community. But it seems to me that even students of a lower proficiency level could benefit from training around summarizing skills. As Shih (1992, p. 307) points out, summary writing is excellent practice for tests with an essay component. And in a few months from now, my students will be heading off to university, many of them to major in English, and they will be asked summarize texts as well as sit for tests with essay questions, regardless of whether such tasks and tests could be considered level appropriate or not.

So since the students came back from summer break I tried out some summary skills building classes. The classes were 90 minutes in length. Here’s a rough outline of how I prepared, what I did in class, and how things went down:

1. Preparation and article selection:First I chose an article with a clear chronological story line, something that would be easier to summarize than say an article on global warming which might require students to not only keep track of key ideas, but a incongruous time line as well. I settled on “Election Day,” a ~250 word simplified news article about a man trying to become the mayor of his town. Here is the first paragraph:

The Election

Herb Casey wants to be mayor of his city. So he works hard. He puts up signs. “VOTE FOR HERB CASEY,” the signs say. He knocks on doors and talks to people. “Please vote for me,” he says. He mails letters to thousand of people. “Please vote for me,” he writes. He gives speeches. “Vote for me!” he says in his speeches.

— Heyer (2004)

2. Vocabulary/word and phrase comprehension:instead of pre-teaching vocabulary, which has it’s advantages, I passed out a worksheet which contained the full ~250 word article. When making the worksheet, instead of a standard font I used a dotted font, the type usually reserved for writing practice. I had the students read the first paragraph and the first paragraph only. As they read, they were instructed to trace over every word they knew. In this way students were left with a nearly completed paragraph. I find drawing students attention to what they can do as opposed to what they can’t (such as by having students circle the words they don’t know) usually starts us off on a better psychological foot. I also read the text out loud to the students. At lower levels, students often fail to recognize words that they actually know and produce in speech. I was pretty thrilled when two of the students, after hearing the word ‘election’ pronounced, traced the word on their worksheet.

3. Comprehension check/main point examples: Next I gave students a question which, if answered well, would naturally lead to a summary of the paragraph’s contents. I got this idea from Simcock’s (1990) ask and answer technique (and there’s a pretty good write up in this Paul Nation article http://www.melta.org.my/ET/1991/main1.html), which is an oral activity to build fluency activities, but which is highly adaptable for written work. I also provided a series of yes/no statements.

[image: student notes]

As you can see, I did a bit of paraphrasing and word substitution within these answers. Out of 14 students in the class, all fourteen marked the correct yes/no box for each answer. I did have to give a bit of a description of the phrase ‘face to face’ and link it up with the idea of ‘knocking on doors’ from the paragraph from the text. While overall this seems like a basic comprehension question/activity (and of course it is that), it also helps provide examples of what constitutes main ideas in a paragraph and how word substitution is perfectly acceptable when paraphrasing.

4. Increasing text familiarity/use of structures within the text: Now that I was pretty sure students had comprehended the text, I really wanted to give them a chance to actually do a bit of production work with the text. But I was pretty sure they weren’t ready to jump into writing a summary yet. I decided to do a read/think/say + listen/think/writeexercise (Fanselow, n.d.). Students were put in pairs. One student was the reader, the other the writer. The reader would read as much of the texts as they could easily commit to memory, at which point they would turn the paper over, count to three, and say the memorized portion of the text to their partner. The listener, pen on table, would wait until the reader finished speaking, count to three, pick up their pen and write what they could on the paper. If they wanted, they could ask the reader to repeat what was said. But the reader could not provide assistance in the form of suggesting missing words, spelling corrections, etc. After the paragraph was completely transcribed in this manner, students compared what they had written to what was on the paper. They circled any differences in red. Now some of the changes made were perfectly acceptable substitutions or simplifications. For example, one student took the sentences, “He gives speeches. ‘Vote for me!’ he says in his speeches,” and changed it to, “He gives speeches and says, ‘Vote for me.'” So not only does the read/think/say + listen/think/writehelp students memorize a text by giving it a chance to loop around in short-term memory (West as cited in Nation, 2009a, p. 67), it also helps students notice that they are already have the skills necessary to paraphrase, an important component of summarizing.

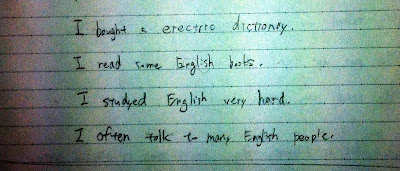

5. Personalization: I think one of the biggest hurdles to students producing a decent summary is the distance they feel with the text material. Even the article used for this class, while having a strong narrative thread and being wildly slightly more interesting than your average academic paper, was content-wise, still pretty far away from my students’ daily life. If students were talking about themselves, they would have little trouble using the grammar structures or even most of the vocabulary found in the article. A personalization activity is another way to help show students that they already have many of the skills they need to write a summary. In this case, I helped students personalize the grammar by asking them to answer the question, “How did you do to become a good English speaker?” The following is one student’s answers:

6. Production of first summary: well, it’s been a long process. It took about 60 minutes of class time to get here. For this step of the process, I had the students put away all the materials we had used up to this point and erased the white-board. Then I wrote the sentence, “Herb Casey wants to be mayor of his town…” and started soliciting sentences to put in our summary. What I ended up with was:

Herb Casey wants to be mayor of his town. He works very hard. He puts up signs. He talks to lots of people. He asks people for their votes.

7. Winnowing it down: Chambers and Brigham (as cited in Nation, 2009a) suggest a process of winnowing away a text with a group of learners, deleting elaborating sentences, unnecessary clauses from main sentences, and finally any remaining unnecessary words. It seems like a great idea for showing higher level students how to carve their way to a decent summary. But I also think it requires a pretty complete comprehension of the text and wouldn’t work very well with lower level students right off the bat. But as a final step in this process, it worked quite well and only took about 5 minutes in total. By this point of the process, students were really primed to simplify and came up with the following:

Herb Casey wants to be mayor of his town so worked very hard. He puts up signs, talked to lots of people and asked for their votes.

The entire process from start to finish took seventy-five minutes. But the next day, when I ran the class again, it took a total of 40 minutes per paragraph.

Modifying the process:

Like the act of summarizing itself, one of the benefits of using a detailed, step by step process like that above, is the fact that it can be simplified and condensed. Both comprehension checks and personalization were put aside when students in my class were working to summarize the third paragraph within “The Election” article. And once students can summarize articles with a strong linear narrative, they can be exposed to different and potentially more difficult genres of text, such as simplified government reports or academic articles. And when exposed to a new genre, steps which had become superfluous with previous genres can be reinserted as necessary.

As Newman and Strever (1997) say, “if a student can decipher the meaning of an article, differentiate the main ideas from the details, and transfer that knowledge into writing, then many teachers would feel the student has understood the material.” By helping even lower-intermediate students develop the skills necessary to summarize, we provide both ourselves and them with an important tool to measure their comprehension of a text. But more than that, we are preparing them for the ways in which they will be using English in the future. Because waiting to teach a set of skills until they have suddenly become necessary for language production, is a recipe for a classroom with an overabundance of stress, an emotion better left out of a summary of any successful language classroom.

References:

Fanselow, J. (nip). Albabka fur: tapping students’ positive feelings about oral reading and overcoming their dread of the activity.

Heyer, S. (2004). The Election. All New Easy True Stories: A Picture-Based Beginning Reader. Pearson Longman.

Kirkland, R. & Saunders, M. (1991). Maximiing student performance in summary writing: managing cognitive load. TESOL Quarterly 25 (1): 105-121

Nation, I.S.P. (2009a). Teaching ESL/EFL Reading and Writing. Routledge: New York.

Nation, I.S.P. (2009b) Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking. Routledge: New York.

Newman, K. & Strever, J. (1997). Using electronic peer audience and summary writing with ESL students. Journal of College Reading and Learning 28 (1): 24-

Shih, M. (1992). Beyond comprehension exercises in the ESL academic reading class. TESOL Quarterly 26 (2): 289-318

Yes – teaching summarising is not as simple as it sounds!I like your read/think/say+listen/think/write. I have often used "running dictation" for similar effect, but battle the inventiveness of young Chinese (for example) with mobile phones photographing the text and then showing it to their partners and other youngsters (I won't say what nationality!) ripping the paper off the wall to share with their partner.I have also found useful for this the "Two articles" activity (as offered in the old bogglesworldesl.com)where they have to read a short article, remember the 'facts', and then (without recourse to the original article)impart the knowledge to a partner who then has to past a test on that info (and vice versa). They always do so much better the second time they try the activity.Anyway, I like your thinking.

LikeLike

Great post Kevin. I have sometimes struggled getting across summaries to the kids. Really like how you approached this. I love how you got them focusing on what they can do rather than what they can't.I'm going to try put many of the ideas into practice. I will have to adapt due to having a total of 25 minutes, but already feel better equipped to approach summarising skills. Congrats on your 50th post. Top quality, as always.

LikeLike

Ruth,Thanks for the comment and I'm very impressed with your students effort to exert no effort. They would definitely get better returns out of their creativity, if they just directed it what they were supposed to be doing.Love the "Two Articles" activity. I haven't used it since I moved to my new school (4 years ago) and totally misplaced it in my mental file cabinet. Thanks for the reminder. And I agree that when it comes to summarizing, one time is definitely not enough. Running the same exercise twice is almost a necessity.Thanks again for visiting the blog and leaving a comment,Kevin

LikeLike

Hi Barry,Thanks for the feedback. When it comes to students summarizing a simple article, I'm always surprised by how few of their hard earned skills students bring to the task. Once students realize the can do these things, the supporting activities can slowly be cut out. But that feeling of "I can do it" needs to be cultivated first I think.Would love to hear what steps you use in your 25 minutes and thanks so much for the good wishes.Kevin

LikeLike

Hi Kevin, I agree with Barry and Ruth!Once again you've tackled a complex subject, that so many of us deal with, in a clear and comprehensive manner. Here in Korea the school system has decided to push summarizing for the exact same points you mentioned. The gist of which turns out to be teachers giving students books to read, students try to summarize, and then i get to grade. Needless to say, there is room for improvement.I especially enjoy how you help the students highlight what they already know and get everyone off on a positive start. It is also super helpful to remember that any idea or "step by step procedure" can be amended to suit our needs. I certainly do not have 90 minutes classes, but can surely take some bits and bobs out and work within the constraints I am faced with.Cheers for another great idea! That makes AT LEAST 3 I've taken off you. My only hope is one day I may have a brilliant idea to share and give you one to take for yourself 🙂

LikeLike

Hi John,I appreciate the praise and probably should take a moment to say that most of the ideas in this post are taken from my program goals, goals which were crafted by John Fanselow and discussed at length with all the teachers in the program. So while it seems that the summarizing skills building process was built by me, actually it was the result of sending out emails with a draft plan and getting feedback like, "Seems like you are just teaching them what to do in this activity, can you change it around so students can use skills they already have." Anyway, I'm glad that there were some useful steps in here and would love to hear what worked for your students. And I really dig your blog. The honest you bring to reflecting on what is happening in your classes makes for gripping reading and helps me recast what's going on in my own classes.KevinAnd for any teacher reading this, if you haven't checked it out, be sure to visit John's blog at: http://observingtheclass.wordpress.com/

LikeLike